Kiln technology in the Mayen pottery district around 500 AD

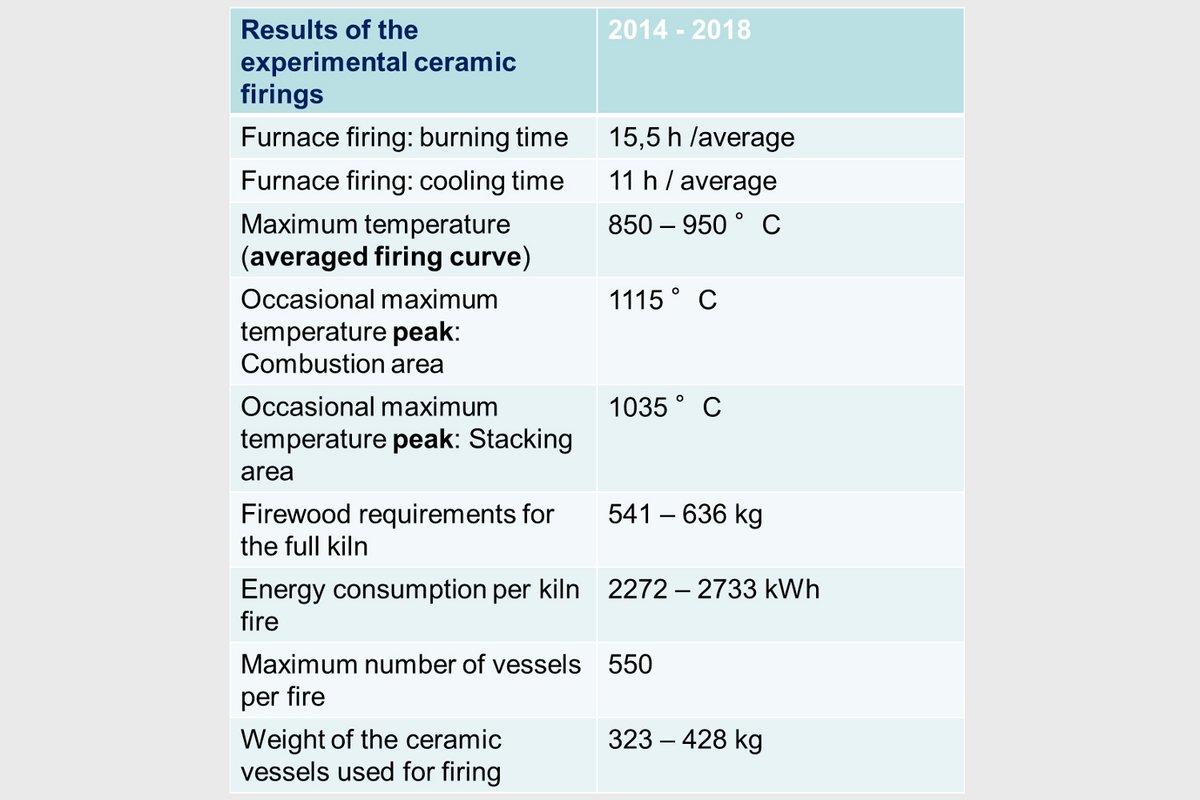

The research objective is to obtain transparent data from the experimental operation of a Mayen chimney kiln from around 500 AD, which can be used in the development of quantification models for productivity. In the analysis of the data, each kiln with its operating personnel is regarded as an independent production unit. The further integration of the results into superordinate social and economic historical contexts will take place within the framework of the overall project on the kiln technology of the Mayen potteries. For the experimental archaeological evaluation, kiln types were selected whose construction principles were decisive for kiln building over several centuries or marked important developmental steps in Mayen pottery production. From the late fifth century onwards, standing shaft kilns were the established and dominant production facilities of the Mayen pottery trade. Around 480/90 AD, this type of kiln construction appears for the first time in Mayen in the pottery area “Siegfriedstraße 53” (kiln 500). The construction principle continued to be used in Mayen throughout the Merovingian period. The latest proof of operation of this type of construction comes from the property at Siegfriedstraße 6-8 and dates to the late 8th/9th century. The productivity of the reconstructed Kiln 500 was tested between 2014 and 2018 under changing questions. In the process, data on basic operating parameters such as firing times, weight load of the threshing floor, wood and energy consumption were collected and incorporated into a quantitative operating model.

- Copy link

- Print article

Contact

- Dr. Michael Herdick

- +49 6131 8885-671 -654

- Kontakt

Team

- Erica Hanning

- Dr. Lutz Grunwald

- Anna Axtmann

Project Period

- 01.2014 - 12.2018

- Döhner u. a. 2018: G. Döhner – M. Herdick – A. Axtmann, Ofentechnologie und Werkstoffdesign im Mayener Töpfereirevier, Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Bilanz 17, 2018, 71–86. Online: https://www.academia.edu/37514000/Ofentechnologie_und_Werkstoffdesign_im_Mayener_T%C3%B6pfereirevier_um_500_n._Chr

- Döhner u. a. 2020: G. Döhner – M. Herdick – A. Axtmann, Technical-Historical Comparison of Pottery Districts: Desiderata and Experimental Archaeological Research Prospects, in: M. Herdick – Angelika. Hunold – H. Schaaff (Hrsg.), Pre-modern Industrial Districts, Panel 3.12, Archaeology and Economy in the Ancient World 14 (Heidelberg 2020) 39–52

https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.726 - Döhner u. a. 2021a: G. Döhner – M. Herdick – U. Katschmareck – A. Axtmann, Kommentierte Messdiagramme zur spätantiken Töpferofentechnologie. Zum Nutzen langfristig angelegter experimentalarchäologischer Evaluierungen historischer Töpferanlagen., in: M. Gierszewska-Noszczyńska – L. Grunwald (Hrsg.), Zwischen Machtzentren und Produktionsorten. Wirtschaftsaspekte von der römischen Epoche bis in das Hochmittelalter am Rhein und seinen Nachbarregionen, RGZM-Tagungen 44 (Mainz, im Druck) 91-104

https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.996 - Döhner u. a. 2021b: G. Döhner – M. Herdick – U. Katschmarek – A. Axtmann, Überlegungen zum wirtschaftsgeschichtlichen Potenzial der Experimentellen Archäologie: Entwurf eines Betriebsmodells für einen spätantiken Schachtofen des Mayener Töpfereireviers., in: M. Gierszewska-Noszczyńska – L. Grunwald (Hrsg.), Zwischen Machtzentren und Produktionsorten. Wirtschaftsaspekte von der römischen Epoche bis in das Hochmittelalter am Rhein und seinen Nachbarregionen, RGZM-Tagungen 44 (Mainz, im Druck) 69-91

https://doi.org/10.11588/propylaeum.996 - Hanning u. a. 2014: E. Hanning – G. Döhner – L. Grunwald – M. Herdick – A. Hastenteufel – A. Rech – A. Axtmann, Die Keramiktechnologie der Mayener Großtöpfereien: Experimentalarchäologie in einem vormodernen Industrierevier., Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums 61, 2014, 339–378,

https://doi.org/10.11588/jrgzm.2014.1.72416 - Hanning u. a. 2016: E. Hanning – G. Döhner – L. Grunwald – A. Hastenteufel – A. Rech – A. Axtmann – A. Bogott, Experimental Reconstruction and Firing of a 5/6th Century Updraft Kiln from Mayen, Germany, Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Jahrbuch, 2016, 60–73. Online: https://www.academia.edu/34690580/Experimental_Reconstruction_and_Firing_of_a_5_6th_Century_Updraft_Kiln_from_Mayen_Germany

- Herdick 2020: M. Herdick, Protagonists and Localisations of Authenticity in Museums: A Case Study of the Experimental Archaeology of the Mayen Pottery, in: D. Kimmel – S. Brüggerhoff (Hrsg.), Museen - Orte des Authentischen? - Museums - Places of Authenticity? Beiträge internationaler Fachtagungen des Leibniz-Forschungsverbundes Historische Authentizität in Mainz und Cambridge, RGZM-Tagungen 42 (Mainz 2020) 303–312. Online: https://www.academia.edu/44474531/Protagonists_and_Localisations_of_Authenticity_in_Museums_A_Case_Study_of_the_Experimental_Archaeology_of_the_Mayen_Pottery_

Technical key figures resulting from the experimental operation of the Mayen shaft kiln between 2014 and 2018 are summarised in the table. From the operating model developed, it can be deduced that about 8,640 containers per year can be fired in a shaft kiln with an operating team of five people. With a misfiring rate of 6%, around 8,122 vessels per operating unit could then go on sale. In summary, therefore, a production unit can produce the vessels for a kiln setting relatively quickly and thus regularly recurring kiln firings during the working year are also guaranteed. Therefore, there is sufficient time for clay extraction and preparation as well as fuel procurement. Through the cooperation of several production units, the use of synergy effects and a stronger division of labour, productivity could be increased even further. For example, with a two-week firing cycle, 12,960 cooking pots and jugs would have been fired annually. Detailed description of the operating model: (Döhner et al. 2021b).

![[Translate to Englisch:] [Translate to Englisch:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/c/3/csm_2_ofenwand_woelbtoepfe_c88482591f.jpg)

![[Translate to Englisch:] [Translate to Englisch:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/9/b/csm_1_ofenbesatz15_782910678a.jpg)